Amélie BARBIER-GAUCHARD[1] and Mathilde FRANCOIS[2]

[1] Enseignant -chercheur au BETA, University of Strasbourg, France,

Email : abarbier@unistra.fr, Twitter : @barbiergauchard, Website : http://www.barbier-gauchard.com,

[2] Student in Master Degree in Macroeconomics and European Policy at the Faculty of Economics and Management University of Strasbourg, France

As the European Union seeks to boost all possible engines of economic growth, education is among the key factors for a smart and inclusive growth. The start of the new school year is an ideal time to look at the different ways in which education systems operate in Europe. This article provides an overview of national education systems in the European Union, particularly for primary and secondary education

What kind of educational systems coexist? An institutional point of view

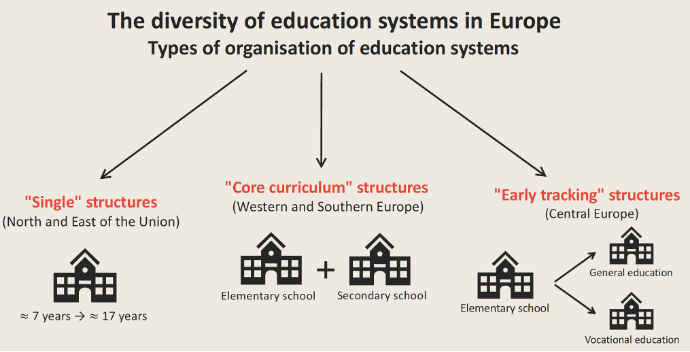

In the European Union, 3 kinds of national educational systems coexist as illustrated by Figure 1: “single”, “core curriculum” or “early tracking” structures. In “single” structures, a general education is provided by a single institution for the whole schooling. They concern the North and the East of the EU (Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia). “Core curriculum” structures are also characterized by a general education but provided by two institutions: primary and secondary schools. Western and Southern Europe apply this organization: France, United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Romania, Greece. In “early tracking” structures, pupils are oriented at the end of primary school towards general or vocational education. This is the defining feature of Germany in the same way as Austria, Lithuania, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. In Germany, vocational education is seen as a pathway to excellence contrary to France. The duale Ausbildung system allows students to alternate between an in-company training and the vocational school. Furthermore, relationships between school and production are very close; Germany has the lowest unemployment rate in Europe after this course (the unemployment rate was around 6% in Germany in April 2021). It should be noted that in the East of the EU, “single” and “core curriculum” structures coexist (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Latvia).

What are the main differences?

Comparisons of education systems are numerous, and a large number of indicators can be selected, leading to a large wide of conclusions. Here we have chosen to focus on four of them to illustrate the extreme complexity of cross-country comparisons: average class size, teacher recruitment methods, the trend in public spending on education since 2010 and Importance to fundamental knowledges (reading, writing, mathematics, sciences).

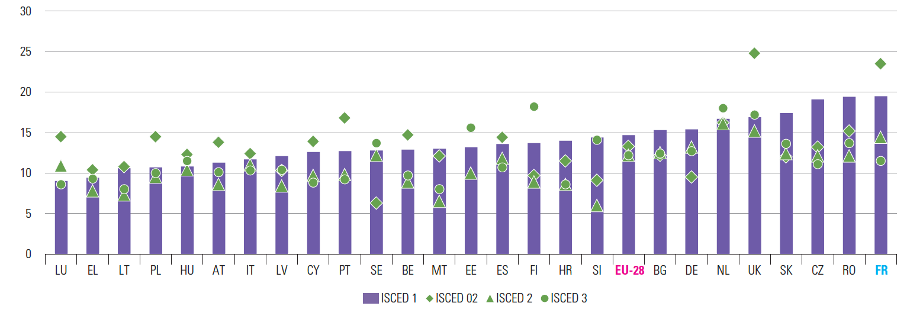

Ratio of students to teaching staff: The average class size provides information on the number of pupils per class as shown by Figure 2. Luxembourg has the lowest ratio in primary education (ISCED1) with 9 students per teacher. Greece, Lithuania, Poland and Hungary have also a favorable ratio in primary (less than 11 students per teacher) while France has the highest ratio (more than 19 pupils per teacher). About the lower secondary education (ISCED 2), the United Kingdom has the highest ratio (25 students per teacher). France is ranked 2nd with more than 23 pupils per teacher. At the same time, Sweden, Slovenia, Germany and Finland a have favorable ratio (fewer than 10 pupils). In upper secondary education (ISCED 2), the French pupil-teacher ratio (11) is better than the European average (12).

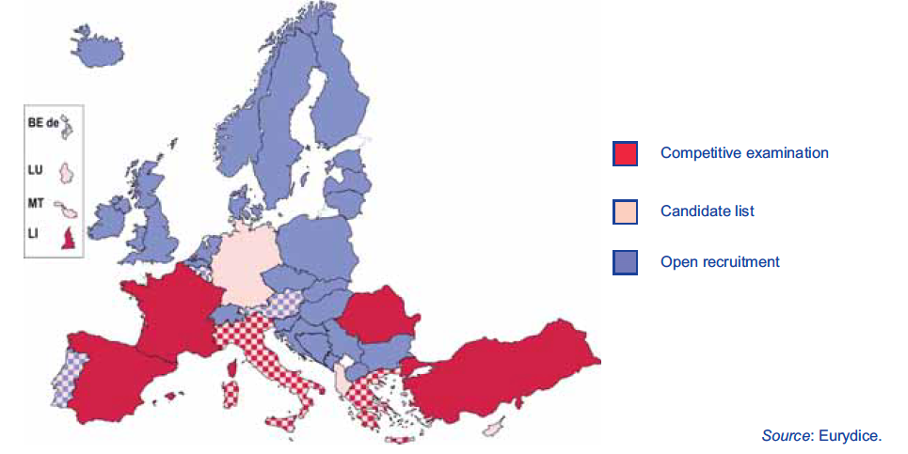

Main methods of recruiting fully qualified teachers: Three types of teacher recruitment for a first appointment coexist: open recruitment, competitive examination and candidate list. Figure 3 illustrated the situation in the EU. In almost three quarters of countries, open recruitment is the most used method (Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom, Ireland, Switzerland, Netherlands…). The selection of the best candidates is decentralized: it is made by schools and sometimes in collaboration with local authorities. The process can be highly regulated (i. e. selection criteria, recruitment procedure) or not. Competitive examinations organized by public authorities at higher, regional or local levels is the second method. In France, Spain, Romania and Liechtenstein, the competition is the only method of teacher recruitment. In Greece and Italy, candidate lists are increasingly used in addition to examinations. The “candidate list” is the third kind of recruitment. Candidate teachers apply for a job application with a top or intermediate authority and are ranked according to defining criteria. For instance, in German, newly qualified teachers address their request to the Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs or to the school supervisory authority. It depends on Länder. The decision is taken centrally on the basis of job vacancies, qualifications and achievements. In Albania, there is two ways to recruit teachers: the e-platform “Teachers for Albania” which ensures transparency in recruitment and the candidature to a local education unit. Other countries such as Cyprus, Luxembourg or Belgium, Austria and Portugal use this method.

Source : Birch, Balcon and Bourgeois (2018), A. Teaching careers in Europe: access, progression, and support. European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018.

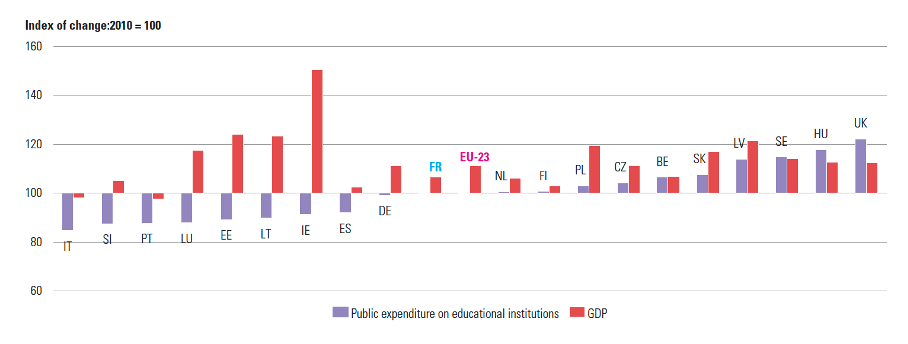

Trend in public spending on education: The evolution of public expenditure on education appears to be highly contrasted across the EU and in many cases uncorrelated with the evolution of GDP as highlighted by Figure 4. The United Kingdom increased it significantly between 2010 and 2016 (by 22 points while its GPD increased less). France, German, Finland and the Netherlands are very close to the European average with a rise of GDP but a stagnation of public expenditure. In comparison, countries like Spain, Estonia, Luxembourg significantly reduced their public expenditure.

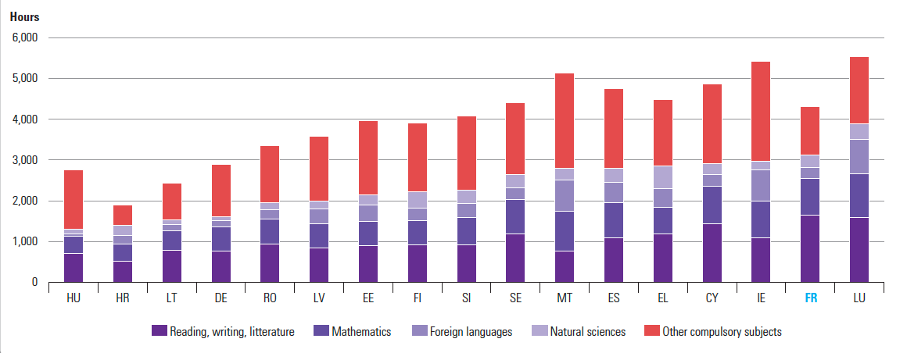

Importance to fundamental knowledges (reading, writing, mathematics, sciences): Figure 5 puts in light the main features of national educational system. During primary education, France is the country which allocates the most hours to reading, writing and literature (around 1 660 hours). Luxembourg is the country which devotes the most hours to mathematics: around 1 060 hours). In these two subjects,Croatia devotes the least hours: around 520 hours to reading, writing and literature and 420 hours to mathematics. Malta is unique because it allocates more hours to mathematics (around 980 hours) than to reading, writing and literature (around 760 hours). Finally, Germany (around 100 hours) and Lithuana (around 110 hours) devote the least hours to natural sciences. A few countries (Austria, Croatia, France and Malta) include social sciences (history, geography) in this subject.

What about performance indicators of the primary and secondary education system?

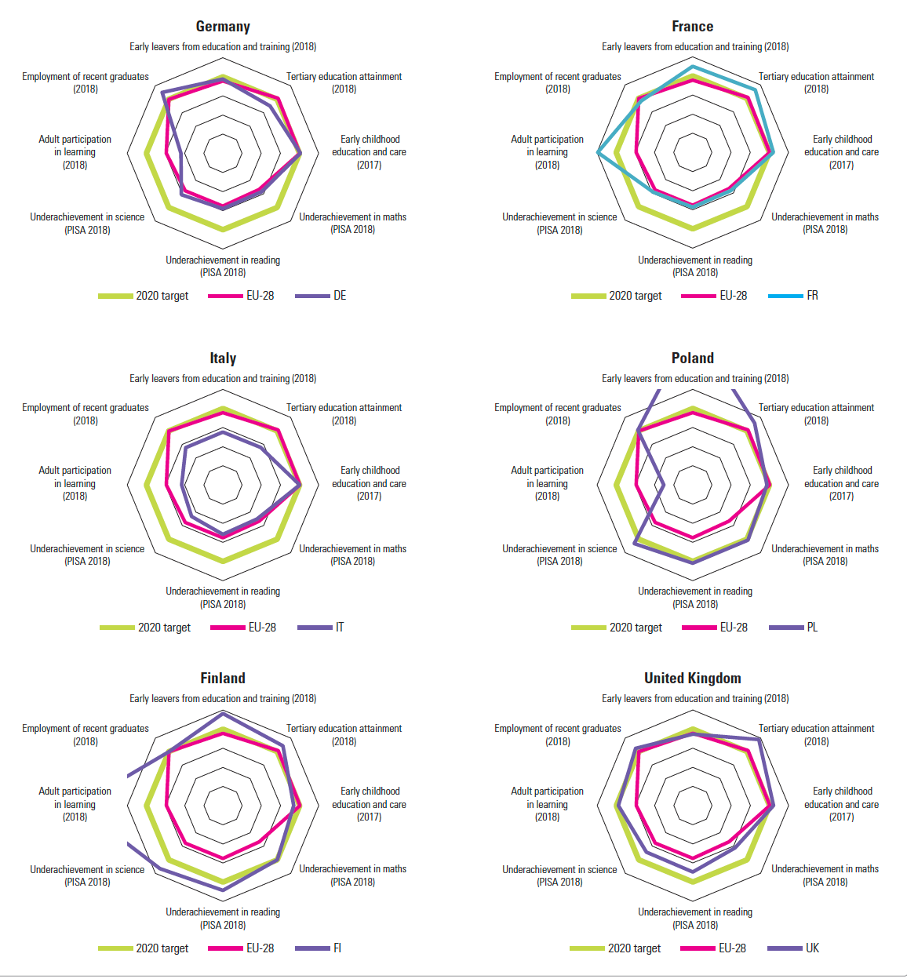

PISA (Program for International Student Assessment), carried out by OECD, is the largest international study which try to measure academic performance of students. It allows to assess the different education systems and comparisons. The study is conducted every 3 years with 15-year-olds. Students realized three tests: a reading comprehension test, a mathematics test and a science test. Figure 6 give some examples of this scoring, especially regarding underachievement in reading, in maths, in science for six EU countries.

Strangely, France seems to be far from the target in terms of reading and mathematics, even though we have shown that it devotes the largest amount of time in the EU to these subjects. It is true, however, that classes seem to be full and that public spending on education has been stagnant for almost 10 years. In contrast, Poland is well on target, with a focus on small classes. In both cases, teachers are recruited on a competitive basis. On the other hand, Germany is in the same situation as France in terms of performance, quite far from the objectives, while it devotes much less time to learning reading and mathematics. But what are the factors that explain this performance? And are these indicators satisfactory for assessing the quality of the education system?

Are these PISA indicators satisfactory?

In the light of these results, there appears to be considerable uncertainty about both the factors that explain educational system performance and the measurement of performance. The aim here is to highlight some elements that are not taken into account by these performance indicators for the education system.

Indeed, the PISA indicators do not consider the nature of the distribution of public and private expenditure on educational institutions. In the United Kingdom, private funds make up around 45% of educational expenditure (in 2017). They represent between 30% and 35% of expenditure on educational institutions in in Portugal, and around 30% in Lithuania and Spain. As contrast, Luxembourg, Norway, Finland and Denmark have a private expenditure on education of 5% or less. Finally, in France, private funds constitute a little less than 20% of the total expenditure in education. The way in which private education systems operate and select students can have a considerable impact on these performance indicators.

Furthermore, these Enrolment in early childhood education could also play a major role. France, Ireland and United Kingdom have the highest enrolment rate in pre-primary education (ISCED 0): 100% in 2017. Denmark, Belgium, Spain and Norway have also high rates (a little less than 100%). At the same time, the lowest rates are found in Switzerland (around 50%), Slovak Republic (a little less than 80%), Finland (around 83%) and Poland (around 85%).

In addition, these indicators do not consider the social inclusion mission of the education system, while social inequalities can have a considerable impact on pupils’ ability to learn. According to the European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education (EASIE), “an inclusive setting refers to education where the learner with Special Education Need (SEN) follows education in mainstream classes alongside their mainstream peers for the largest part – 80% or more – of the school week. In primary and lower-secondary education (ISCED 1 and 2), Ireland (98,98%) and Italy (95,95%) have the highest enrolment rates in inclusive education (based on the enrolled school population). Similarly, Malta (99,47%), Bulgaria (99,45%), Norway (99,36%), Spain (99,28%), Luxembourg (99,25%), Serbia (99,19%) and Sweden (99,09%) have favourable rates. In contrast to these countries, Belgium (80,72%), Hungary (89,47%) and Slovakia (93,81%) have the lowest enrolment rates in inclusive education. Regarding upper-secondary education (ISCED 3), Spain and the Netherlands have an enrolment rate of 100%. Italy (99,98%), Estonia (99,79%), France (99,72%), Greece (99,59%), Latvia (99,44%), Bulgaria (99,43%), Cyprus (99,23%), Luxembourg (99,09%) and Serbia (99,04%) have also encouraging rates. However, Belgium (60,98%), Hungary (84,79%) and Portugal (92,22%) have the lowest enrolment rates in inclusive education.

Should the EU be more involved in the quality of the European education system?

To date, the European Union has had very little involvement in the functioning of primary and secondary education systems. Is this something to be welcomed? Should we be concerned? Should learning the basics (reading, maths, science) at the end of primary and secondary education be considered a European public good? If so, should we seek to harmonize national education systems or should we consider diversity as an asset to be nurtured while ensuring the acquisition of these fundamentals?

Education is an explicit European issue since the Maastricht Treaty (1992). However, the Erasmus Programme (1987) is testament to a European intervention before 1992. In addition, the Lisbon Treaty (2000) and the schemes “Education and Training 2010” and “Education and Training 2020” are demonstrations of European policies in education. The Lisbon Treaty aimed to make the EU “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world”. “Education and Training 2010” was in the same direction with further objectives such as sustainable economic development and social cohesion. Then, “Education and Training 2020” paid particular attention to early school leavers; tertiary education attainment; early childhood education; level of proficiency in reading, mathematics and science (PISA); lifelong learning; employment of recent graduates. But these are only general objectives for the EU and will not further explore and analyze national practices in order to exchange good practice in this area.

Sources :

Birch, Balcon and Bourgeois (2018), A. Teaching careers in Europe: access, progression, and support. European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018.

Farrugia and alii (2020), Education in Europe: Key Figures 3rd edition 2020.

Ramberg and alii (2018), European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2020. European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2018 Dataset Cross-Country Report.