Investing in the Future of the European Union: Lessons from the Canadian model

Amélie Barbier-Gauchard[1] and Marine Gauchard[2]

Introduction

With the European Commission having recently presented its proposal for the 2028–2032 budget, the European Union is facing a set of unprecedented challenges. This paper investigates how fiscal autonomy and territorial solidarity are reconciled within two distinct governance architectures: the European Union (EU) and Canada. In light of mounting geopolitical challenges, including the prioritization of security and defence, we underscore the critical importance of education and healthcare as pillars of social cohesion and long-term growth. While the European Pillar of Social Rights (2017) commits to safeguarding fundamental social rights, pronounced disparities persist among Member States. These divergences are compounded by national fiscal constraints, despite instruments such as Next Generation EU, introduced to bolster post-pandemic recovery. We analyze the fiscal frameworks of these systems, focusing on mechanisms of redistribution and coordination[3], and propose insights for the EU inspired by federal practices, particularly Canada’s equalization system.

Comparative Fiscal Governance: European model versus Canadian model

Despite their institutional differences, both Canada and the EU must manage a core challenge of multi-level governance: how to distribute fiscal powers and financial resources across levels of government in a way that preserves both autonomy of the entities and cohesion.

Institutional Architecture: Two system of authority

Canada’s institutional framework has a classical federal schema where both the federal and provincial governments derive their powers from the Constitution. Provinces enjoy significant autonomy not only in policy-making but also in taxation. They can take personal and corporate income taxes, consumption taxes and property taxation. For instance, Alberta has the lowest rates where Quebec has the highest with a difference of up to an additional 20%. In contrast, the EU is not a political federation but a supranational union of sovereign States. If it exercises an increasing influence in certain areas of public finance, particularly through cohesion policy, it has no general taxation powers. The EU budget remains small and is financed primarily through national contributions[4]. This creates a structural asymmetry: while the EU sets common rules and priorities, its ability to act directly through public spending is highly constrained.

Multi-level governance of public finance refers to the way fiscals responsibilities, resources, and decision-making are shared and coordinated across different levels of government. In both federal and supranational systems, it raises fundamental questions about who collects revenue, who decides how it is spent, and how fiscal rules and transfers are managed to ensure coherence, equity, and efficiency. The challenge is to balance autonomy with national or collective objectives, while maintaining overall fiscal sustainability and territorial fairness.

Financial dependence and autonomy limits

This divergence in institutional structure translates into different types of financial dependence. In Canada, even though provinces are fiscally autonomous on paper, their actual capacity to deliver public services varies significantly. Less wealthy provinces depend heavily on federal transfers to ensure comparable levels of public services across the country. The Equalization Program, plays a central role in balancing interprovincial disparities in fiscal capacity.

In the EU, financial dependence takes another form. Member States remain in charge of raising almost all public revenue and executing most spending. However, less developed regions depend more on European Structural and Cohesion funds. These transfers are vertical, conditional, project-based, and subject to co-financing requirements and EU oversight mechanisms.

These contrasting models of fiscal autonomy and financial capacity directly influence how intergovernmental solidarity is organized in both systems.

Public expenditure patterns: the originality of the European model

This comparative analysis covers the 27 EU Member States, the EU budget, the Canadian federal government and provincial budgets. To ensure consistency in the comparison, we rely on a common analytical framework[5]. To present all the data from this comparative study, we have chosen to rearrange the European typology of the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which presents policy areas in seven main headings. In this analysis, we have considered six main headings and have undertaken various adjustments in order to integrate all the COFOG[6] policy areas to account for all public expenditure of the government entities considered in this study (national level in the case of the EU, and both federal and provincial levels in the case of Canada).

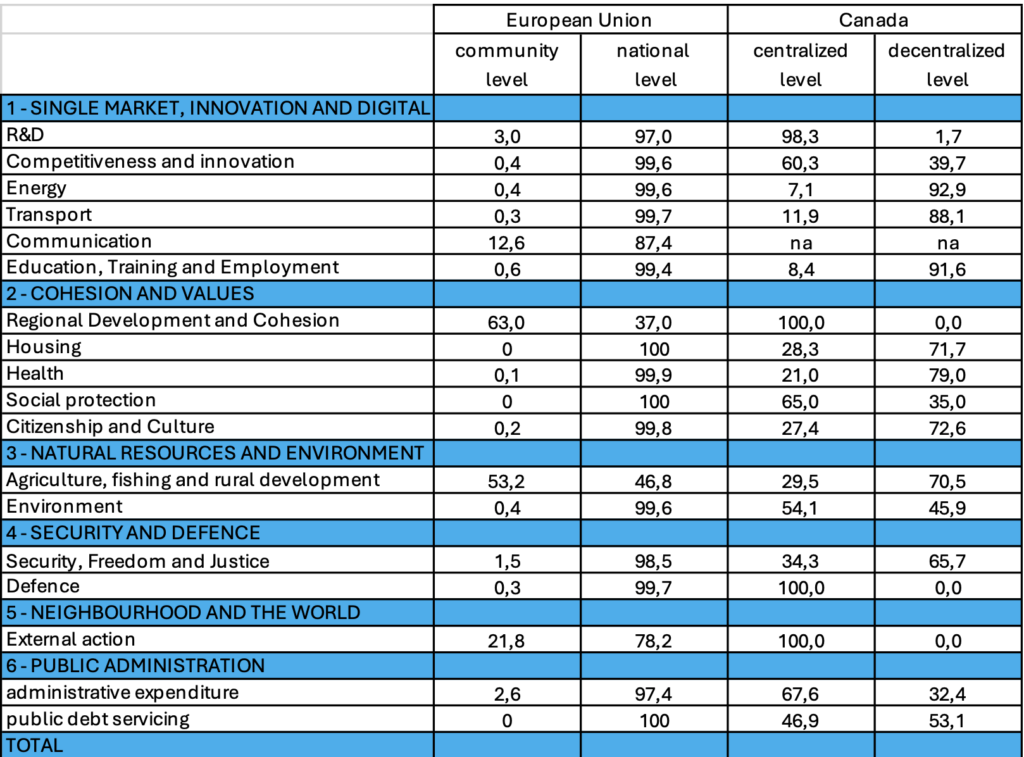

Table : Allocation of total public expenditure by area of intervention and by level of administration as percentage of total public expenditure (2023)

Source : Authors (see methodological appendix)

This comparative approach allows us to distinguish three types of public spending:

(1) highly decentralized public spending in both the EU and Canada: education, training, and employment; health; housing; transportation; citizenship and culture; freedom, security, and justice, etc.

(2) highly centralized public spending in both the EU and Canada: regional cohesion; agriculture, fisheries, and rural development.

(3) highly centralized public spending in Canada but not in the EU: R&D; competitiveness and innovation; energy; defence; and external relations.

It is ultimately these areas of public action that are the focus of the debate in favour of greater Europeanization. The Canadian model also seems to support this.

Redistributive mechanisms and conditionality: two divergent models

While fiscal autonomy defines the margins of action of subnational entities, the other side of multi-level governance lies in the way solidarity is organized. Both Canada and the European Union have developed complex systems to redistribute resources across territories, but they are based on different system and instruments.

Two models of territoriality solidarity

Canada’s approach to solidarity is based on a system of federal transfers. The central instrument is the equalization transfer, which aims to ensure that all provinces, regardless of their economic strength, can offer a comparable level of public services at similar levels of taxation.[7] The Equalization Program, financed entirely by the federal government and enshrined in the Constitution Act (1982, s.36), transfers unconditional payments to provinces whose fiscal capacity, is below a national average. This fiscal capacity is not based on actual tax revenues but on a hypothetical calculation: how much revenue a province could raise if it applied national average tax rates to its own tax bases (personal and corporate income, consumption taxes, natural resources, property taxes, etc.)[8]. Finally, the federal government provides two conditional transfers in key policy areas: the Canada Health Transfer and the Canada Social Transfer. These are also financed through federal revenues and allocated on an equal per capita basis to all provinces and territories. They serve to support national coherence in areas under provincial jurisdiction, particularly healthcare and social services[9]. They come with fewer constraints than EU-style cohesion funds, reflecting the Canadian balance between fiscal solidarity and provincial autonomy.

Similarly, the EU operates on the basis of vertical solidarity such that transfers are made from the EU budget to less developed regions. The main tool is the Cohesion Policy that works through structural and investment funds (ERDF, ESF+, Cohesion Fund). These funds are project-based, co-financed and highly conditional, with ex-post evaluations.

Institutional system of redistribution

In Canada, solidarity is executed through the federal budget alone. Provinces do not contribute directly to equalization, the program is entirely financed and administered by the federal government. However, debates persist, because equalization can be seen as an incentive not to make an effort to develop because in case of development the fiscal capacity will increase and therefore the transfer will be lower, it can be seen as a sort of perverse effect. The calculation of fiscal capacity is regularly contested, and equalization remains a sensitive political issue. The federal equalization program is not tied to specific policy outcomes or service standards. However, its constitutional objective is explicit: “to ensure that provinces have the fiscal capacity to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation” (art 36, Constitution Act). This goal is not measured through performance indicators, because in practice, no federal mechanism evaluates whether this equity is achieved, and provinces have full discretion in how they allocate equalization funds.

In the same way as the equalization in Canada, there is a financial equalization program in Switzerland. The purpose is to reduce disparities between cantons with regard to financial capacity and to guarantee the cantons a minimum allocation of financial resources. Both system are very similar with the aim to reduces disparities and the absence of conditionality with no specific affect needed. This makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of the transfer.

In the EU, solidarity is set in a collective and negotiated process, where all member states contribute and all receive something in return. The funds are not managed directly by the EU but through a shared management system, where the European Commission approves programs that are co-financed, and then implemented by the member states and their subnational authorities. The EU’s approach to solidarity remains highly codified, conditional, and strategic, combining financial redistribution with policy alignment and structural reforms.

Key divergence: conditionality and control

One of the most striking differences between Canada and the EU is found in the degree and nature of conditionality attached to financial transfers. In Canada, equalization payments are unconditional: provinces can use the funds as they wish, without federal intervention in how they spend them. This reflects a strong constitutional commitment to provincial autonomy and the politically sensitive nature of federal–provincial fiscal relations. In addition to this non-conditionality, there is a lack of control so that the federal government does not make evaluation or does not look at the way in which equalization is used. There is real freedom left to the provinces.

In contrast, in the EU, conditionality is central to the design of solidarity mechanisms. All major cohesion policy instruments are governed by ex-ante eligibility criteria, and ex-post-performance evaluations. Regional and national authorities must submit detailed operational programs, comply with EU regulatory frameworks, and co-finance projects with their own resources. The European Commission not only approves these programs but also monitors implementation; to encourage financial discipline and timely implementation, the EU applies mechanisms whereby funds not used within a defined period are returned to the EU budget.

Addressing disparities in Education and Healthcare

Overview of disparities in education and healthcare across Member States in the EU

Despite common values and objectives, the quality and accessibility of public services – particularly in education and healthcare – varies significantly across EU member States. These inequalities challenge the Union’s objective of ensuring access to similar level of public services.

Education gaps

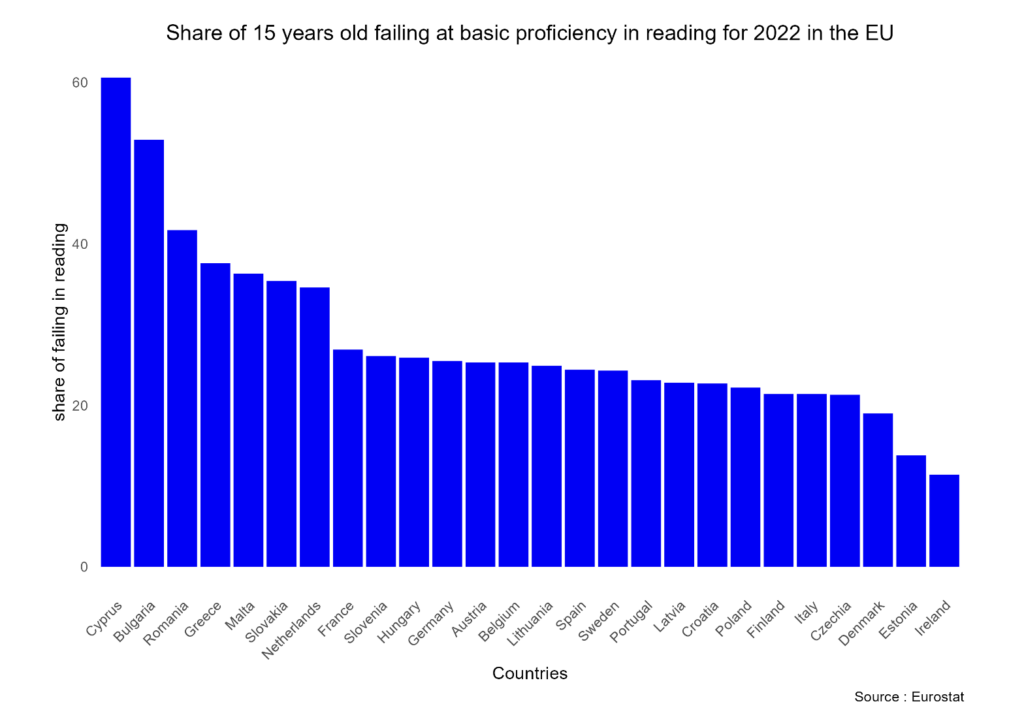

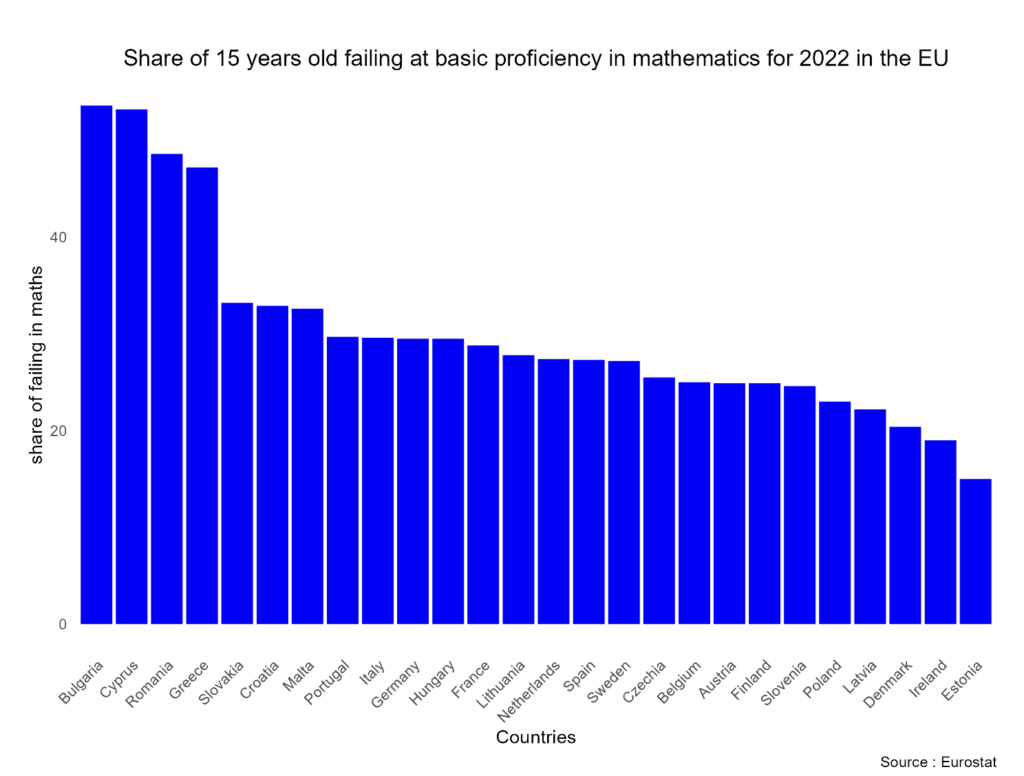

Education outcomes vary widely across EU countries, reflecting both structural differences and unequal policy performance. As far as basic skills proficiency are concerned (PISA 2022), the share of 15-year-old failing to basic proficiency in reading, mathematics, and science reached 15,7% in Ireland, but as high as 55,2% in Cyprus, revealing a dramatic gap in foundational education outcomes (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 :

Figure 2 :

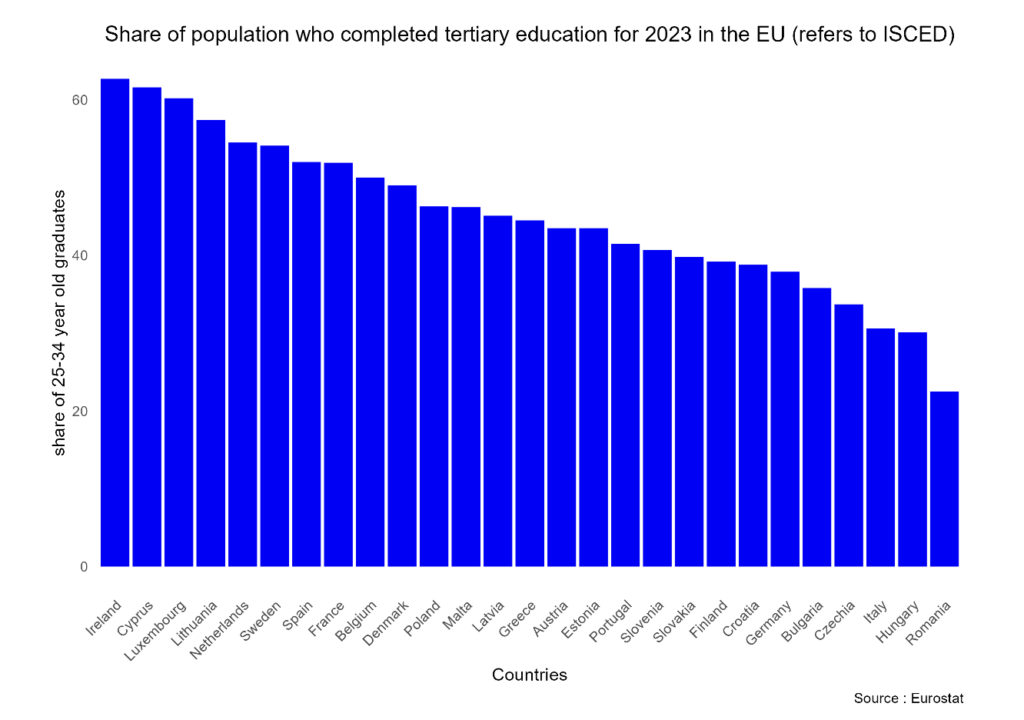

For completion tertiary studies, in 2023, the share of young adults (aged 25–34) having completed tertiary education ranged from 22,5% in Romania to 62,7% in Ireland (ISCED classification) (figure 3).

Figure 3 :

Healthcare: Divergence outcomes in access and quality of care

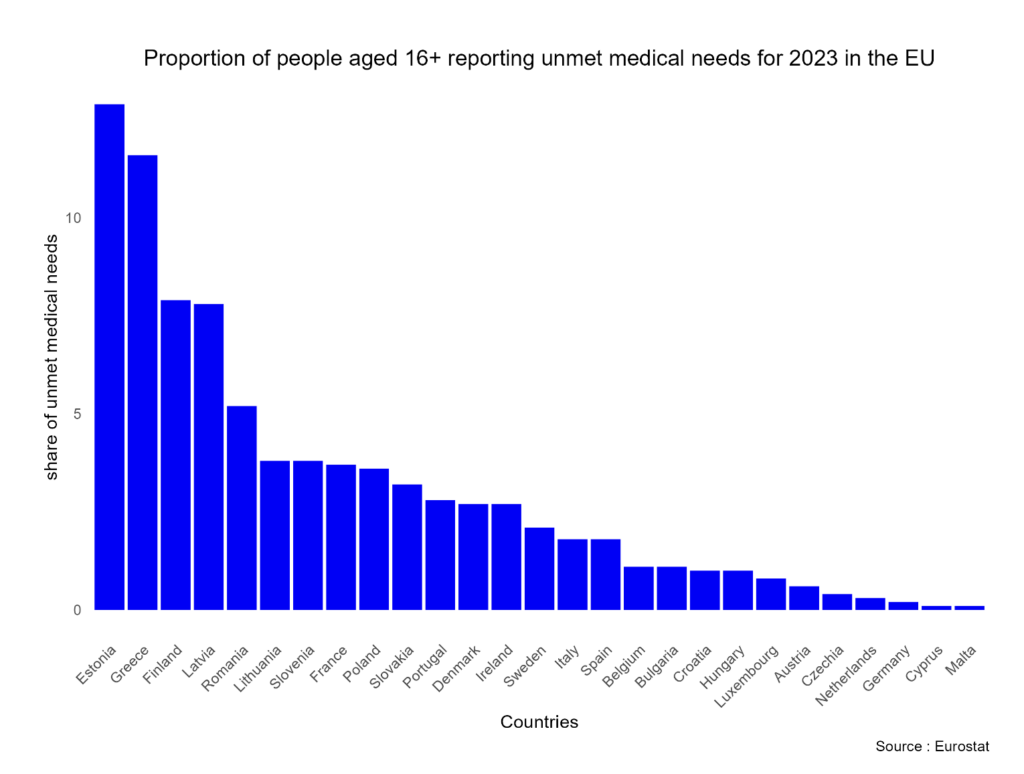

Concerning unmet medical needs, the proportion of people aged 16+ reporting unmet medical needs due to cost, distance, or waiting time was just 0.2% in Germany, but reached 12.9% in Estonia (figure 4).

Figure 4 :

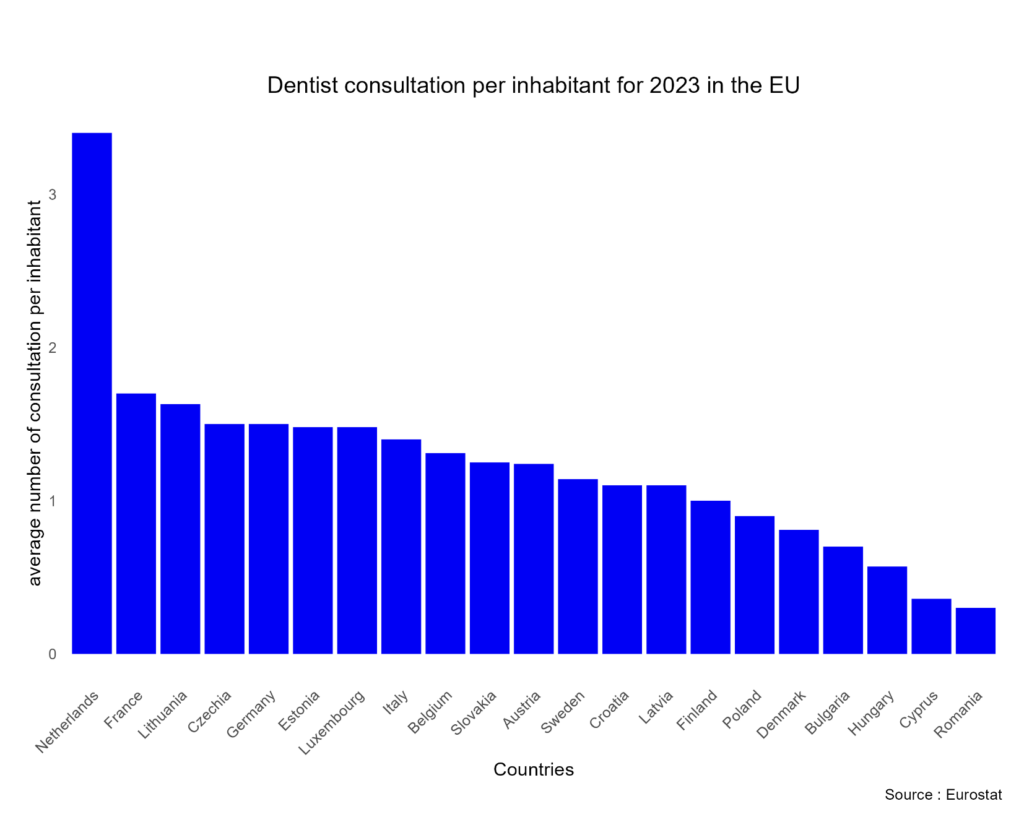

As for access to dental care, the average number of dentist consultations per inhabitant varied greatly, from just 0.05 in Cyprus to 3.30 in the Netherlands, revealing sharp disparities in access to preventive oral health services (figure 5).

Figure 5:

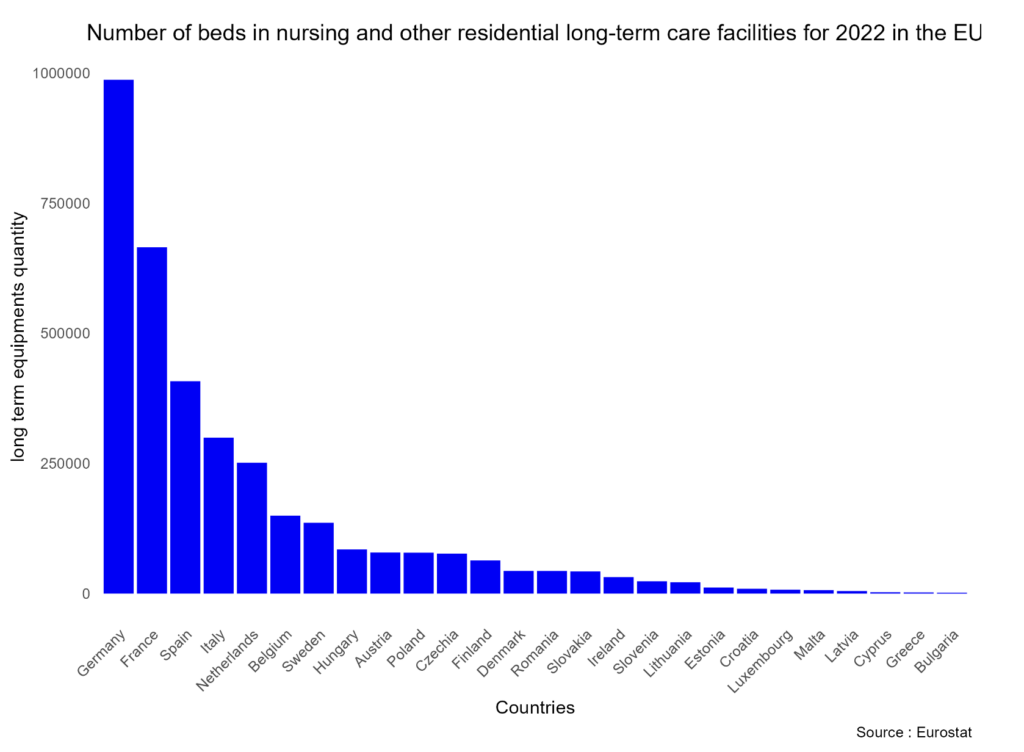

For long-term care equipment, the number of beds in nursing and other residential long-term care facilities ranged from 1,679 in Bulgaria to 993,097 in Germany, pointing to major differences in care capacity for dependent persons (figure 6).

Figure 6:

Health indicators also show considerable divergence between member States, whether in terms of perceived health status, preventable deaths, or access to care. These figures, drawn from Eurostat, reveal a marked heterogeneity in public service performance across EU member states, particularly in education and healthcare. This fragmentation persists despite a shared commitment to social cohesion and the objective of building a more equitable European social model, as expressed in the European Pillar of Social Rights.

This raises a fundamental question: if the EU aims to ensure fair access to quality public services across its territory, should financial solidarity mechanisms be based not only on economic development gaps, but also on a more precise assessment of each country’s fiscal capacity? Drawing inspiration from federal models such as Canada or Switzerland, it becomes useful to examine whether a common method for evaluating the fiscal potential of member states could help better target EU funds and reinforce upward convergence in service delivery.

Advocating conditional transfers calibrated to the fiscal capacity of Member States

Tax systems across the EU are highly fragmented, with significant differences in tax rates and overall tax effort. For example, corporate income tax rates range from 9% in Hungary to over 30% in some Western countries. These divergences reflect national choices, but they also make it difficult to compare countries’ fiscal capacity on the basis of actual revenues.

A simulation-based approach that applies common average tax rates to national tax bases, would offer a more comparable measure of each country’s potential to fund public services. This could allow EU cohesion policies to focus not only on economic output, but also on what each country can reasonably raise through taxation.

So, in the Canadian equalization system, a province’s fiscal capacity is calculated by applying average tax rates to its own tax bases (personal income, corporate profits, consumption, property, natural resources). This approach estimates a theoretical revenue, independently of local policy choices or actual tax effort. Transposing this logic to the EU would involve the following steps:

- Identifying comparable national tax bases across member States, such as personal income, corporate profits, or household consumption.

- Applying EU average tax rates to each member State’s tax base, in order to simulate how much revenue a country could theoretically raise under a harmonised tax structure.

Such an approach would mirror the logic of comparable services for comparable tax level, as set out in the Canadian Constitution. The result would be an indicator of simulated fiscal capacity, comparable across countries, and independent of actual tax rates, exemptions, or administrative effectiveness. This could allow the establishment of a more transparent and legitimate system of fiscal solidarity, based not only on income disparities (GDP per capita), but also on the structural capacity of a country to finance public services.

Conclusion

By comparing the fiscal and solidarity architectures of the European Union and Canada, this report highlights both profound differences and potential sources of inspiration. The EU, as a union of sovereign States, remains limited by the absence of direct taxation powers and by a relatively small budget, which restricts its capacity to act in key areas such as health, education, and social protection. Canada, as a fully-fledged federation, relies on robust equalization mechanisms and federal transfers that, while imperfect and sometimes contested, ensure a degree of territorial cohesion and budgetary solidarity far beyond what the EU currently provides. This comparison underlines the importance of rethinking redistribution instruments and of considering a stronger EU role in guaranteeing equitable access to essential services for all citizens.

From this perspective, the Canadian experience suggests that the EU should reform its solidarity mechanisms by moving beyond GDP per capita as the sole criterion, and by incorporating the concept of theoretical fiscal capacity of Member States. Introducing conditional transfers calibrated to this fiscal capacity, inspired by Canada’s model, could enhance both the legitimacy and effectiveness of EU cohesion policy, while reducing persistent disparities in education and healthcare. Such steps towards a more integrated governance would not undermine national autonomy but would provide the EU with the necessary tools to consolidate its social and political project in the face of multiple challenges, from demographic ageing to geopolitical tensions. Investing in renewed and credible solidarity thus appears as a necessary condition for building a more cohesive, equitable, and future-oriented Europe.

[1] Corresponding author :abarbier@unistra.fr, full professor in Economics, University of Strasbourg, France.

[2] Research assistant (May to July, 2025), University of Strasbourg, France.

[3] A. Barbier-Gauchard (2008) Intégration budgétaire européenne – Enjeux et perspectives pour les finances publiques européennes, éditions De Boeck.

[4] A. Barbier-Gauchard, M. Sidiropoulos, A. Varoudakis (2018) la gouvernance économique de la zone euro : réalité et perspective, éditions De Boeck.

[5] see methodological appendix.

[6] COFOG (Classification Of the Functions Of Government) is an international classification that breaks down data on public administration expenditures from the System of National Accounts according to the different objectives or functions for which the funds are used.

[7] D. Béland, A. Lecours, G.P. Marchildon, H. Mou, R. Olfert (2017) Fiscal Federalism and Equalization Policy in Canada: Political and Economic Dimensions, University of Toronto Press.

[8] In parallel, a separate but similar transfer mechanism – the Territorial Financing Formula – supports the three northern territories, where geographical remoteness and demographic challenges generate higher public spending needs and limited own-source revenue potential. This transfer is also unconditional and federally funded, shaped to the specific structural challenges of these regions.

[9] D. Béland, A. Lecours, T. Tombe, E. Champagne (2023) Fiscal federalism in Canada : Analysis, Evaluation and Prescription, University of Toronto Press.