Fiscal policy transparency

Work carried out by the students of Master 2 in Economics

Victor Barat

Estelle Campenet

Edeline Chopard-dit-Jean

Alex Gumustas

Sarah Rosen

Célia Stammler

On December 9, 2022, the Vice President of the European Parliament was arrested with five people for a corruption case regarding the Football World Cup in Qatar. This affair calls into question the transparency of European institutions, but not only. Agents necessarily become more suspicious of opaque institutions, sometimes leading to uncertainty. In particular, we can be interested in the transparency of economic policies, and more precisely in the transparency of fiscal policy.

Government transparency: what does it mean?

According to OCDE (2002, 2015), fiscal policy transparency is the timely and systematic provision of full budget information. Similarly, according to the IMF (2007), fiscal transparency is about providing access to public reports on the past, present and future state of public finances, which should be clear, comprehensive and reliable (Hameed, 2006). Geraats (2002) adds procedural transparency, which is to account for the process of policy-making. In a nutshell, as summarized by the IMF, “fiscal transparency” could be defined as the government ability to give high quality information on how government raise, spend and manage public resources. “Fiscal transparency” is also called “government transparency”, but should be distinguished from “budget transparency”. This wording is more restrictive, and concerns only revenue and expenditure flows.

The concept of transparency in budgetary policy is thus concentrated around the accessibility of accounting documents and the decision-making process. However, the different definitions do not exactly converge. The literature on monetary policy transparency can be used to better understand what the different facets of fiscal policy transparency may be. Indeed, four main dimensions can be identified (Dincer and Eichengreen, 2022): objectives, means, procedure and results.

This analysis grid could be applied to monetary policy. A transparent monetary policy has, in the first instance, a clearly stated objective by the Central Banks, and often an inflation target to reach. Moreover, monetary policy must be transparent about the means it uses to achieve its objective. This can be done through communication channels, such as explaining the increase in key rates. Also, according to Diana (2008), in order to be transparent, the process by which a policy is decided must necessarily be known. In the monetary case, this procedural transparency is not perfectly known, with a grey area regarding the appointment of national Central Bank governors. However, once this stage is over, the negotiations are made public once the political decision has been taken. The final point is that results of monetary policy must be known and accessible. Thus, Central Banks regularly publish their indicator statements (inflation statements, for example).

In the same way, fiscal policy, in order to be transparent, must clearly display its objective: deficit, growth, unemployment, … Furthermore, as monetary policy, the transparency of fiscal policy’s means brings to fiscal transparency. It can be in terms of displaying how governments finance their objectives (i.e. by raising taxes, borrowing, or creating money for countries outside the euro zone). In addition, procedural transparency can be achieved through public participation in decision-making or through a clearly established legal procedure (e.g., Article 49.3 of the French Constitution, Diana, 2008). It seems more complicated to assess the direct results of fiscal policy. Resources are less clear and readable than monetary ones. Although the distribution of budgets among objectives is published, the record of their use is more difficult to access. For example, in the case of a reduction in employers’ contributions to encourage hiring, there is no document summarizing the impact of this measure on employment. However, the influence of fiscal policy on the announced target must be disclosed, even if the expected effect is not achieved.

These various elements can be summarized in the following table:

| Objectives | Means | Procedure | Results | |

| Monetary policy | Display a goal (inflation, economic stability) | Use the communication channels | Make negotiations and appointments public | Publish and make available the results (inflation statements) |

| Fiscal policy | Display a goal (deficit, unemployment, growth) | Be transparent about revenues and expenses | Involve the publicUse a legal procedure | Make the actual results accessible and understandable |

Source: Authors.

A wide range of indicators: interests and weaknesses.

Indicators of fiscal transparency are generally based on the recommendations of good budgetary practice developed by the IMF (2007) and the OECD (2002, 2015), and thus mainly on the concepts of access to documents.

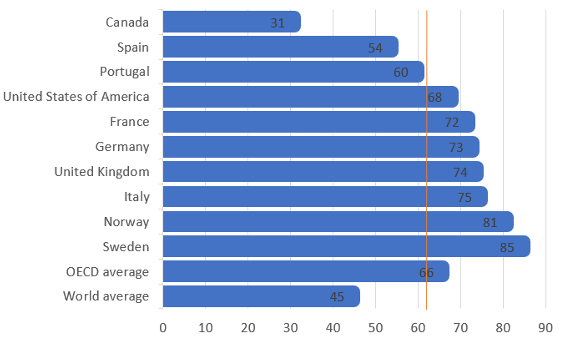

It is therefore on the basis of these recommendations that budget transparency indicators are established, in particular the Open Budget Index (OBI). The OBI was created in 2006 by the International Budget Partnership (IBP)[1]. It is then a civil society initiative. Thus, IBP created the OBI to report on the levels of budget transparency around the world and has produced a study every year since 2006, offering a ranking of countries. This indicator defines budget transparency as the public availability of budget document. The OBI is a composite index, containing three sub-indices, which are public participation, budgetary oversight and transparency. We will focus here only on the last one. It consists of a questionnaire sent to research institutions and civil society organizations about access to some key documents related to fiscal policy. Score are between 0 and 100 points. A country with a minimum score of 61 points is considered transparent according to this indicator (see Figure 1). Of the 120 countries surveyed, the overall average is 45 points, which is below the 61 threshold. For OECD countries, the average is 66. Among developed countries, we can see that Nordic countries are particularly transparent, especially Sweden and Norway, with scores of 85 and 81 respectively. Among developing countries, there are some 0 scores, such as Yemen. Among all developing countries, Jordan is the only country to reach the transparency threshold of 61 points.

Figure 1: Budget transparency in developed countries in 2021 (data from International Budget Partnership, 2021).

Furthermore, there were another indicator to reflect the fiscal policy transparency at the international scale: the Transparency of Government Policymaking Index. It was created in 2007 by the World Economic Forum, also known as the Davos Forum[2], and lasted 10 years. It is an initiative of the World Bank, based on a survey. Company heads are asked to rate on a scale of 1 to 7 the ease of access to public policy change notes affecting their businesses. The closer the index level was to 7, the easier it was for companies to obtain such information in a given country. In 2017, the worldwide median level of this Index reached 4 (see Figure 2). That means that it was rather easy for companies to access government information in the half of the 137 studied countries this year, that is to say in almost 70 countries. At this time, among the countries with a high score, we can find Norway (5.78), Qatar (5.54) and Sweden (5.48). On the other hand, among the countries with a low score, we can observe Yemen (2.52), Egypt (2.96) and Italy (3.07).

Figure 2: Transparency and accessibility of government policies in developed countries in 2017 (data from World Bank, 2017).

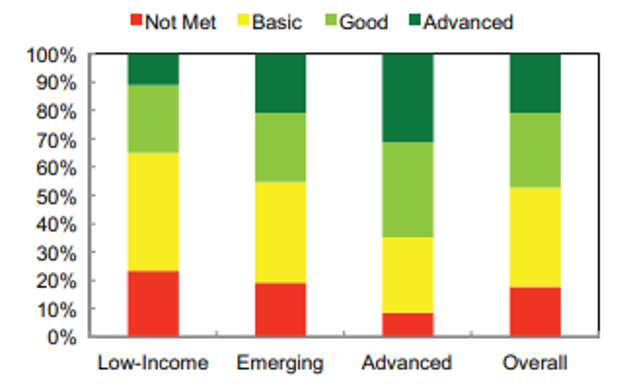

Finally, we can also look at the IMF’s fiscal transparency code. This is broadly the international standard for public financial disclosure. Four pillars structure this code, illustrated below (see Figure 3). It can be noted that most of notions are management’s ones. There is no real macroeconomic measurements. Some 30 countries at all levels of development are currently included in this study. The score of participants is expressed as a percentage. It can be noted that, globally, low-income countries are the least transparent countries (see Figure 4). It can also be noted that overall, more than half of the countries surveyed do not provide good information on their fiscal policy.

Figure 3: Four pillars of the new code (IMF, 2018).

Figure 4: Results by income level (percentage of total scores, IMF, 2018).

One problem with this multiplicity of indicators is that the results and rankings do not necessarily overlap. For example, Qatar’s score on the Transparency of Government Policymaking Index is above the required threshold (5.54 vs. 4), while it is far below the threshold for OBI (2 vs 61). This points to a problem in the actual definition of fiscal policy transparency.

Government transparency and economic policy efficiency: state of art.

Benito et al. (2017) constituted an analysis on the factors of fiscal transparency that have a significant effect on sovereign debt, in particular. They created a transparency index, taking the effective interest rate as the dependent variable combined with a transparency variable. The latter was constructed by the authors using the OECD’s Best Practices in Fiscal Transparency report. This report was written so that both OECD and non-OECD countries would have a tool at their disposal to improve their transparency levels. The results empirically show that fiscal transparency has a negative influence on the national interest rate. In addition, better budget transparency and disclosure would reduce the debt burden. Since financial markets do not have information on the public finances of non-transparent governments, they will penalize them. If governments are seen to be more fiscally transparent, then market access will be facilitated, as financial markets have less uncertainty about the fulfillment of fiscal obligations. This also leads to less information asymmetry, which reduces the cost of financing public finances.

Moreover, Gootjes and de Haan (2022) show that fiscal transparency is essential for fiscal rules to have real effects, and that it increases the probability that adjustments will have lasting effects. Without fiscal transparency, fiscal rules have no effect on the primary budget balance. The authors used panel data from seventy-three countries, both developed and emerging, over the period 2003 to 2013. To obtain their fiscal transparency index, they use an IMF database, taking into account the code of good practices.

El-Berry and Goeminne (2020) define fiscal transparency as the disclosure of fiscal information, the assurance of the quality of that information, public and parliamentary oversight of expenditures, and the monitoring of fiscal risks. This is in the spirit of the IMF’s fiscal transparency code. Fiscal transparency can affect the credibility of fiscal institutions through two channels, which are also found in Montes et al. (2019). These channels are that of public debt and the relative efficiency of public spending. Indeed, public debt is intrinsically linked to fiscal transparency. On the one hand, transparency is linked to political will and therefor to political color. In this case, Alt and Lassen (2005) show that in the OECD, a higher degree of transparency is associated both with lower public debt and with more right-wing oriented governments. Fiscal transparency thus reduces the rate of debt accumulation. On the other hand, since the financial crisis, in order to improve the efficiency of public spending, Montes et al. (2019) show that 80% of developed and developing countries have made notable effort to improve fiscal transparency. Indeed, faced with the magnitude of public spending in this crisis situation, the authorities have had a desire to increase their efficiency, and thus ultimately spend relatively less. Fiscal transparency is therefore important to reduce the long-term public debt. In a contradictory view, we can note Kemoe and Zhan (2018), who identify three aspects of fiscal transparency, namely openness of the fiscal process, transparency of budget data and accountability of budget actors. Greater fiscal transparency under these three notions reduces sovereign interest rate spreads (which therefore converge upward) and increases sovereign debt. On the other hand, through the notion of openness, having access to fiscal data increases the likelihood that foreigners will buy emerging market sovereign debt.

Conclusion.

Finally, the term « fiscal transparency » is subject to much conceptual debate. Moreover, we have seen that the indicators of reality do not completely correspond to the theoretical typology. These are used in the economic literature to include a transparency component. The fact remains that countries have different objectives in terms of transparency. The fact that fiscal transparency indicators are inherently flawed points to the need to improve the perception of the outcome of fiscal policy. In this case, the results of fiscal policy are not given much attention, as opposed to, for example, the ease of access to accounting records. A parallel can therefore be drawn here with the other counterpart of economic policy, namely monetary policy. The latter has objectives with perfectly known results. The transparency of monetary policy is therefore a priori better than that of fiscal policy. Both can inspire and reinforce each other, in order to achieve effective economic transparency, allowing agents to act with the maximum possible knowledge. Moreover, such transparency appears to be a component if the trust and credibility that agents place in institutions, which are essential elements of government effectiveness (Montes et al., 2019; El-Berry et Goeminne, 2020).

Bibliography / Sitography.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. D. (2006). Fiscal transparency, political parties, and debt in OECD countries. European Economic Review, 50(6), 1403‑1439. DOI.

Bastida, F., Guillamón, M., & Benito, B. (2017). Fiscal transparency and the cost of sovereign debt. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(1), 106‑128. DOI.

Code de Bonnes Pratiques de matière de Transparence des Finances Publiques. (2007). In IMF. Link.

Contributeurs aux projets Wikimedia. (2023). Forum économique mondial. fr.wikipedia.org. Link.

Diana, G. (2008). Transparence, responsabilité et légitimité de la Banque Centrale Européenne. OPEE. Link.

Dincer, N., Eichengreen, B., & Geraats. (2022). Trends in Monetary Policy Transparency: Further Updates. International Journal of Central Banking, 18(1). Link.

El-Berry, N. A. M., & Goeminne, S. (2021). Fiscal transparency, fiscal forecasting and budget credibility in developing countries. Journal of Forecasting, 40(1), 144‑161. DOI.

Kemoe, L., & Zhan, Z., (2018). Fiscal Transparency, Borrowing Costs, and Foreign Holdings of Sovereign Debt. (s. d.). Google Books. Link.

Geraats, P. (2002). Central Bank Transparency. The Economic Journal, 112(483). DOI.

Gootjes, B., & De Haan, J. (2022). Do fiscal rules need budget transparency to be effective ? European Journal of Political Economy, 75, 102210. DOI.

Hameed, F. (2005). Fiscal Transparency and Economic Outcomes. DOI.

Montes, G. C., Bastos, J. C. A., & De Oliveira, A. E. F. (2019). Fiscal transparency, government effectiveness and government spending efficiency: Some international evidence based on panel data approach. Economic Modelling, 79, 211‑225. DOI.

OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency. (2002). In OECD. Link.

Pattanayak, S. (2018). Fiscal Transparency Handbook (2018). In International Monetary Fund eBooks. International Monetary Fund. DOI.

Questionnaire sur le budget ouvert 2021. (2021). In International Budget Partnership. Link.

Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance. (2015). In OECD. Link.

Schwab, K., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2016). The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017. In World Economic Forum. Link.

[1] Created in 1997 with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities project, a nonpartisan nonprofit research institute, whose goal was to advocate for more transparent government budget processes.

[2] This Forum is a non-profit organization which aims to improve the state of the World since 1971. The foundation is composed of major politic, economic, and entrepreneurial personalities such as Carlos Ghosn (the former Renault CEO) or Christine Lagarde (the ECB President).